By Rabe Abdalkareem, Olivier Nourry, Sultan Wehaibi, Suhaib Mujahid, and Emad Shihab.

In Joint Meeting of the European Software Engineering Conference and the ACM SIGSOFT Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering (ESEC/FSE). 2017.

Paper / Conference

We saw last time that developers are often wary of introducing new dependencies unless they’re really worth it, due to the inevitable cost of maintenance. Why then do developers also depend on so-called “trivial packages”? The left-pad fiasco of last year brought to light how extreme this situation really is: a package providing 11 lines of code to left pad a string was pulled from npm, breaking thousands of other packages which, directly or indirectly, depended on it.

This is the question which this survey paper sets out to answer. Firstly we get some quantitative analysis of trivial package use across 230,000 npm packages and 38,000 applications, then a survey with 88 Node.js developers trivial packages.

What do we mean by a “trivial package”? The authors randomly selected 16 npm packages with between 4 and 250 lines of code and sent out a survey, which got 12 responses, asking whether each package was trivial or not, and why. Here’s an example, the is-positive package:

module.exports = function (n) {

return toString.call(n) === '[object Number]' && n > 0;

};Based on the survey responses, the authors identified both length and cyclomatic complexity of a package to be contributing factors to its triviality:

Our survey indicates that size and complexity are commonly used measures to determine if a package is trivial. Based on our analysis, packages that have ≤ 35 JavaScript LOC and a McCabe’s cyclomatic complexity ≤ 10 are considered to be trivial.

You can quibble over this definition (I might consider a longer but low-complexity package to be trivial, for instance), but triviality is ultimately a judgement call. No matter what metric the authors pick, there will be some who disagree.

How prevalent are they? The authors fetched the latest version of every npm package as of the 5th of May 2016, giving 231,092 packages, after removing 21,904 with no code. They also fetched all Node.js/npm applications on GitHub, giving 38,807 applications, after filtering out 76,814 with fewer than 100 commits or only one developer.

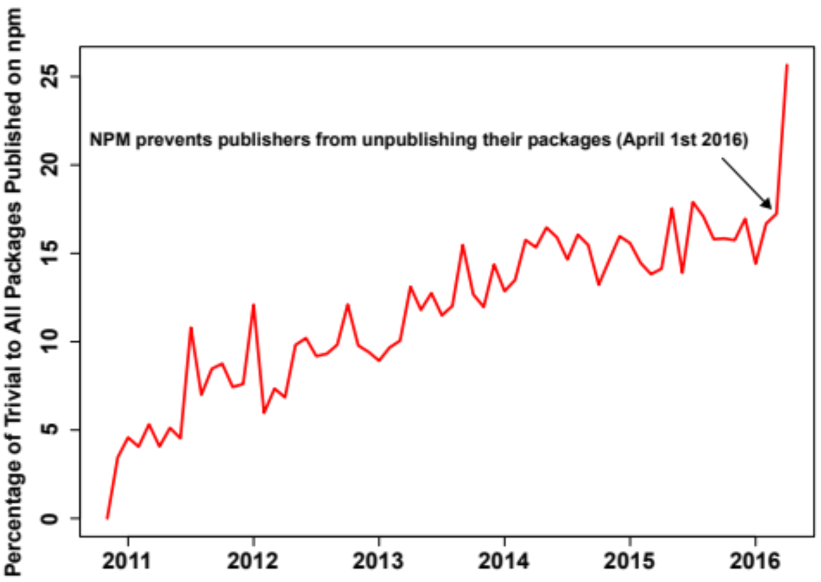

Of the npm packages, an incredible 28,845 (16.8%) are trivial packages. Furthermore, if we look at the proportion of published trivial packages over time, we see that it’s going up! This graph is jagged, up until npm banned unpublishing packages in response to the left-pad incident. I suspect this means that a lot of people used to publish, and then almost immediately remove, trivial packages. Currently, roughly 15% of the packages added each month are trivial packages.

Rather than looking at the entire database of packages, we can also look at the most popular:

npm posts the most depended-upon packages on its website. We measured the number of trivial packages that exist in the top 1,000 most depended-upon packages; we find that 113 of them are trivial packages. This finding shows that trivial packages are not only prevalent and increasing in number, but they are also very popular among developers, making up 11.3% of the 1,000 most depended on npm packages.

When it comes to applications, the authors parsed the source code, looking for import statements, to handle cases where a project’s package.json file (containing metadata for npm to build and run it) specifies a dependency which isn’t used anywhere. This gives, for each application, a set of dependencies which are used:

Finally, we measured the number of packages that are trivial in the set of packages used by the applications. Note that we only consider npm packages since it is the most popular package manager for Node.js packages and other package managers only manage a subset of packages. We find that of the 38,807 applications in our data set, 4,256 (10.9%) directly depend on at least one trivial package.

How do developers feel about them? Given how popular trivial packages are, we might suspect that developers don’t consider them a problem. This is in sharp contrast to some viewpoints in How to Break an API, where developers were wary of introducing new dependencies. This part of the study was conducted as a survey of 88 developers.

The reasons given are:

- Trivial packages provide well implemented and tested code (48 respondents)

- Use of trivial packages increases productivity (42 respondents)

- Use of trivial packages outsources the maintenance burden for that code to the package authors (8 respondents)

- Use of trivial packages helps readability and reduces complexity (8 respondents)

- Use of a trivial package, over a large library or framework, improves application performance (3 respondents)

Only 7 respondents said they saw no reason to use trivial packages.

The authors also asked for the drawbacks of using trivial packages. Now we get some viewpoints closer to How to Break an API. The drawbacks given are:

- The overhead of monitoring dependencies for updates (49 respondents)

- The maintenance burden of breaking changes (16 respondents)

- Decreased build performance, due to the overhead of fetching and building more dependencies (14 respondents)

- Decreased developer performance, due to needing to read more documentation (11 respondents)

- A missed learning opportunity: it’s easier to use a package to solve a problem than to figure it out yourself (8 respondents)

- Potential security risks in third-party code (7 respondents)

- Licensing issues (3 respondents)

Only 7 respondents said they saw no drawbacks to using trivial packages.

Are they well tested? Over half of the respondents said that a reason to use trivial packages is that the code is perceived to be well implemented and tested. But is that really the case?

npm requires that developers provide a test script name with the submission of their packages (listed in the package.json file). In fact, 81.2% (31,521 out of 38,845) of the trivial packages in our dataset have some test script name listed. However, since developers can provide any script name under this field, it is dificult to know if a package is actually tested.

So the authors turn to the npms tool to collect metrics about the trivial packages in their dataset:

We examine whether a package is really well tested and implemented from two aspects; first, we check if a package has tests written for it. Second, since in many cases, developers consider packages to be ‘deployment tested’, we also consider the usage of a package as an indicator of it being well tested and implemented. To carefully examine whether a package is really well tested and implemented, we use the npm online search tool (known as npms) to measure various metrics related to how well the packages are tested, used and valued. To provide its ranking of the packages, npms mines and calculates a number of metrics based on development (e.g., tests) and usage (e.g., no. of downloads) data.

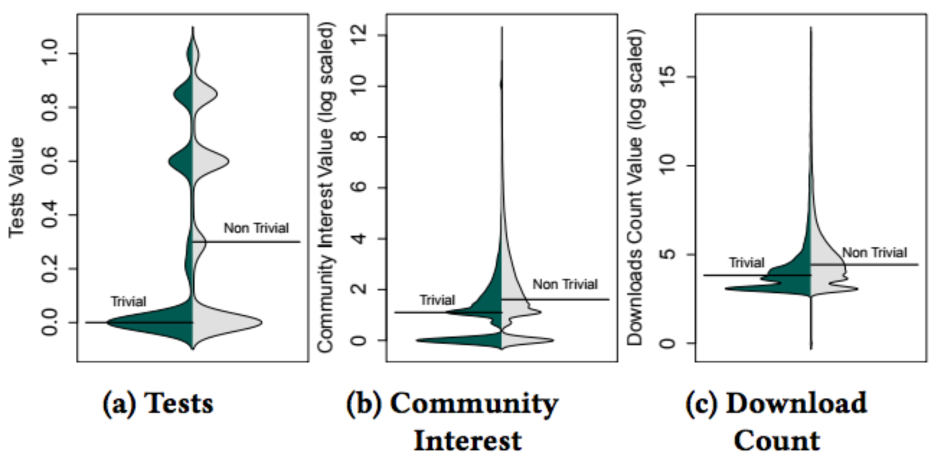

They used three npms metrics to evaluate how tested a package is:

- “Tests”, a weighted sum of the size of the tests, the coverage percentage, and the build status

- “Community interest”, derived from popularity on GitHub

- “Download count”, the number of downloads in the last three months

The results are not so promising:

As an initial step, we calculate the number of trivial packages that have a Tests value greater than zero, which means trivial packages that have some of tests. We find that only 45.2% of the trivial packages have tests, i.e., a Tests value > 0.

So much for well tested!

The authors also compare the metrics of trivial packages with nontrivial packages. We see that the distributions are similar, though nontrivial packages have a greater median, which could easily be due to the size and complexity difference. The authors find that the differences are statistically significant, but with small effect size.

How much effort is needed to keep up with new releases? The most cited drawback for using trivial packages was the extra overhead of needing to keep everything up-to-date.

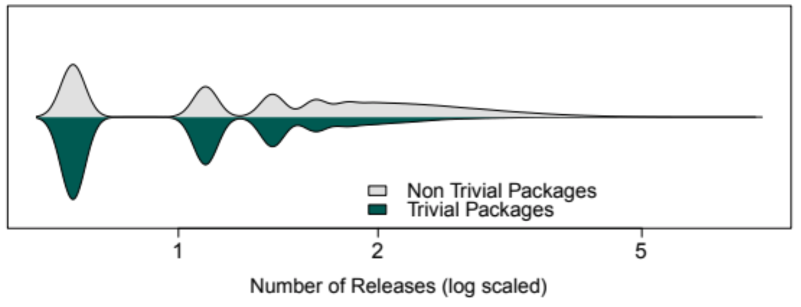

There are a couple of ways to look at the impact of dependencies. Firstly, the authors compare the number of releases. Trivial packages tend to have fewer releases, so it seems that if you’re going to have a dependency, from a purely maintenance perspective, a trivial dependency is the better option.

The fact that the trivial packages are updated less frequently may be attributed to the fact that trivial packages ‘perform less functionality’, hence they need to be updated less frequently

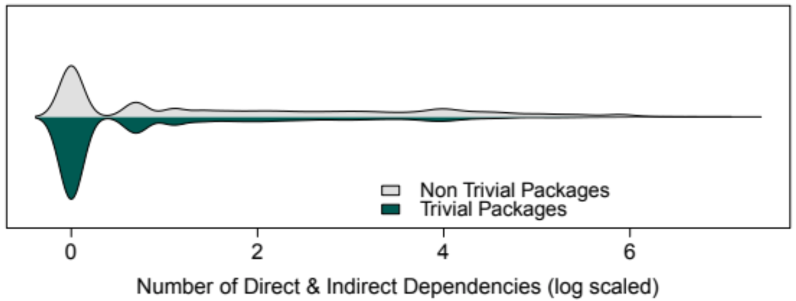

Next the authors consider how many dependencies (direct and indirect) trivial and nontrivial packages have. Introducing extra dependencies increases the complexity of the dependency chain, so all else being equal, we would prefer to have fewer dependencies.

The authors group packages into four categories by number of dependencies:

- 0: 56.3% of trivial packages, 34.8% of nontrivial packages

- 1–10: 27.9% of trivial packages, 30.6% of nontrivial packages

- 11–20: 4.3% of trivial packages, 7.3% of nontrivial packages

- More: 11.5% of trivial packages, 27.3% of nontrivial packages

So developers should beware extra dependencies! Even though the source of a trivial package may be small, it may pull in many additional packages!

Trivial packages have fewer releases and developers are less likely to be version locked than non-trivial packages. That said, developers should be careful when using trivial packages, since in some cases, trivial packages can have numerous dependencies. In fact, we find that 43.7% of trivial packages have at least one dependency and 11.5% of trivial packages have more than 20 dependencies.

The bottom line The final sentence of the paper is short, snappy, and neatly summarises all of what came before:

Hence, developers should be careful about which trivial packages they use.

It probably goes without saying, but I would apply this warning to all packages, trivial and nontrivial.