Dice rolls in Call of Cthulhu

When a PC wants to do something, the GM might call for a roll to see whether they succeed or (if success or failure is a given), how well they do.

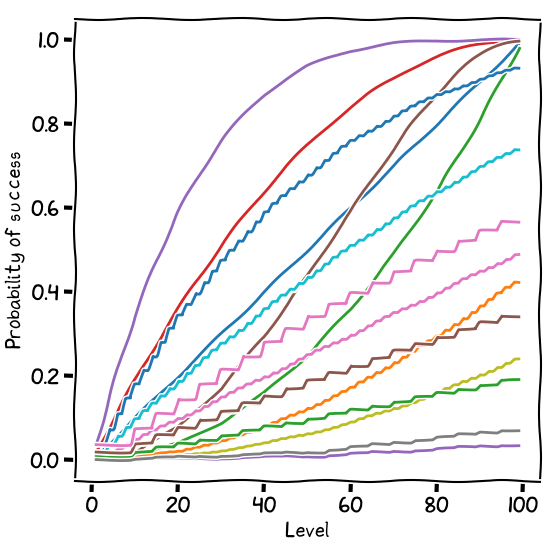

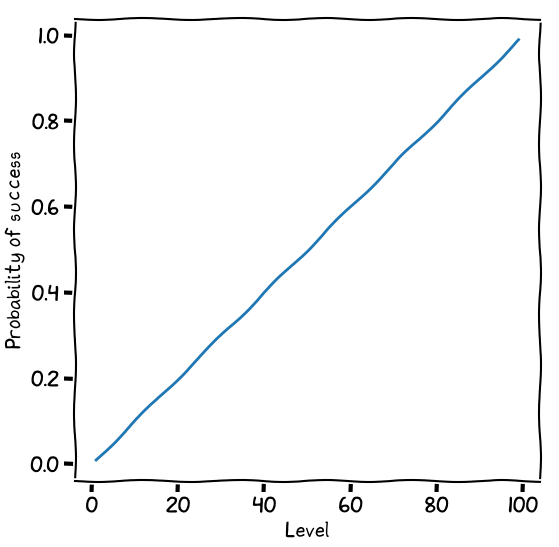

In Call of Cthulhu, the player rolls a pair of percentile dice, succeeding if they roll equal to or below their skill level. The higher your skill, the fewer possible dice results there are above it, so the more likely you are to succeed.

A roll of 1 is always a success and a roll of 100 is always a failure.

Task difficulties

If this was all there were to it, it wouldn’t be very interesting. What if you’re doing something especially difficult? Something that should challenge even an expert?

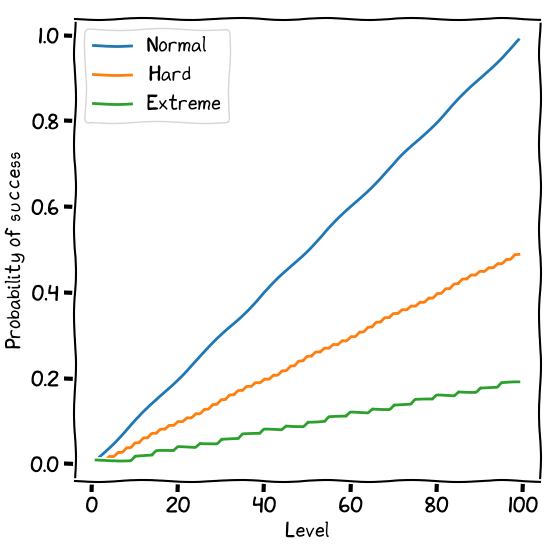

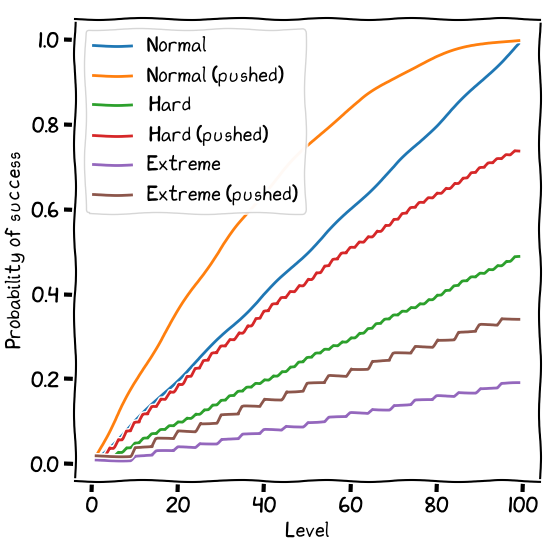

To dial up the intensity, skill rolls have three difficulty levels: normal, which is as above; hard, where you need to roll under half your skill; and extreme, where you need to roll under a fifth of your skill.

Normal rolls are for things that would challenge a competent person. Hard rolls are for things that would challenge a professional. Extreme rolls are for things at the border of human ability.

Trying again

Let’s say our player character Xander is searching for a book about Yig, the Father of Serpents, in an occult book shop. The GM calls for a Library Use roll, and Xander fails. I guess he doesn’t find the book, everyone go back home.

Not quite.

A player can try to push a failed roll, making the roll again, if they can justify it. This isn’t just a re-roll, time always passes between rolls. So perhaps Xander turns the shop upside down, pulling books out of their shelves, risking being thrown out by the shopkeeper (and not being welcome back) or having the police called on him. The consequences of failing a pushed roll should be worse than for a non-pushed roll.

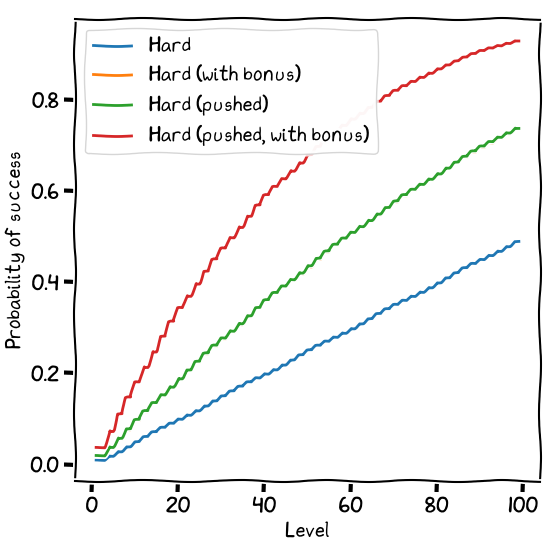

Pushing a roll gives you a better chance at success. It’s no longer linear, there’s a slight curve to the probability.

Situational advantages

Perhaps this shop is blessed with an unusually helpful shopkeeper, or a thorough catalogue, or a clear organisation. In such circumstances, the GM might grant an automatic success.

Let’s say that success isn’t guaranteed though, there is still some additional difficulty which puts the outcome in doubt, even though Xander has this benefit.

To represent this sort of situational advantage, the GM may grant the player a bonus die: an additional “tens” die, where the player keeps the better of the two “tens” values.

The “Hard (pushed)” line completely covers the “Hard (with bonus)” line. Each is as beneficial as the other.

Situational disadvantages

On the other hand, perhaps Xander has an unusually hard time searching for the book. Maybe there’s someone in the shop looking for him, and Xander has to not only find the book but also avoid this other person.

In this case the skill-based task itself (finding the book) isn’t more difficult, so making the skill roll hard when it would have been normal, or extreme when it would have been hard, doesn’t really fit.

To represent this sort of situational disadvantage, the GM may give the player a penalty die. This is exactly the same as a bonus die, but rather than keeping the better of the two “tens” values, the player keeps the worse.

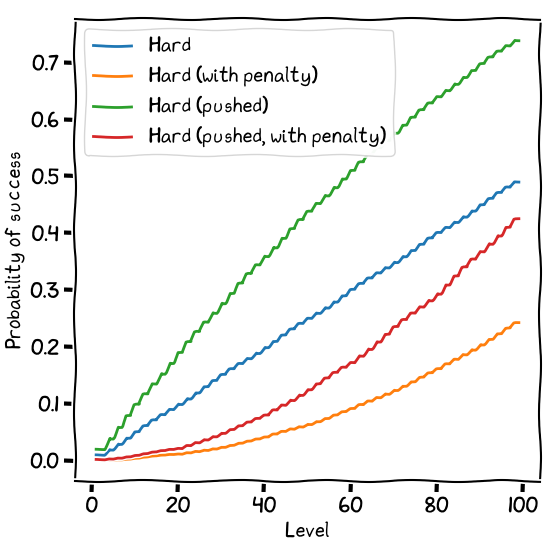

Xander will have a hard time indeed. Even pushing the roll doesn’t fully offset the disadvantage of the penalty die.

Bonus and penalty dice stack, so you could end up with multiple bonuses or multiple penalties.

Going head-to-head

If a PC goes up against someone significant (another PC, or a major NPC), the GM may call for an opposed roll.

Both sides roll, and the side with the greater degree of success (critical > extreme > hard > normal > failure) wins. If both sides achieve the same degree of success, the one with the higher skill wins.

Opposed rolls can’t be pushed.

If the skill of one side is over 100 points greater than the other side (this would normally indicate that they’re not human), they automatically win.

Opposed rolls are the standard in melee combat and for resisting spells, but should only be used for particularly dramatic moments outside of that. Otherwise it could become tedious, and introduce an unnecessarily high risk of failing narratively unimportant rolls.

Let’s flesh out Xander’s shopping trip a bit more:

-

Xander, desperately searching for a spell to banish Yig and aware he is being tailed by one of Yig’s cult, ducks into a small occult book shop.

-

The cultist follows Xander in, but loses sight of him amongst the shelves.

-

The GM calls for a hard Library Use roll with a penalty die; the shop is disorganised, and it’ll be difficult to search while avoiding the cultist.

-

Xander fails. The GM says that the cultist hasn’t found him yet, and that he can push it, but if he fails the pushed roll the cultist will definitely find him.

-

Xander pushes the roll, and fails. He is spotted by the cultist.

-

As the cultist approaches, Xander realises that their skin looks unusually… squamous. It’s not a human cultist at all, it’s a serpent person, one of the leaders of the cult!

-

The serpent person recites a strange chant, and Xander begins to feel overwhelmingly lethargic, and can’t move his limbs.

It’s time for an opposed roll! Xander’s POW against the cultist’s!

Let’s say the serpent person is called Yassith. We’ll assume Yassith’s POW is no more than 100 greater than Xander’s.

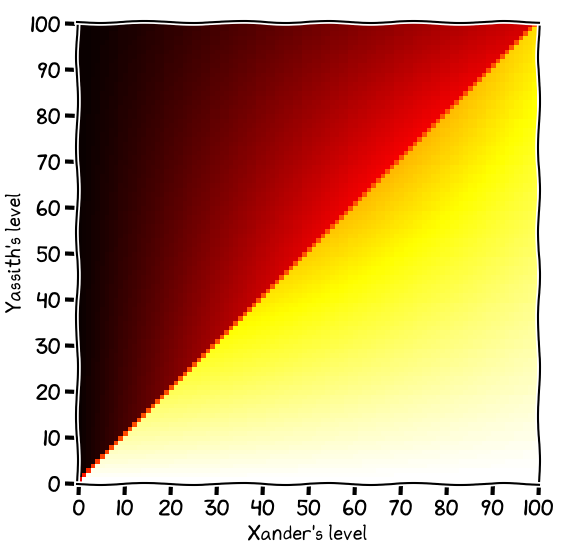

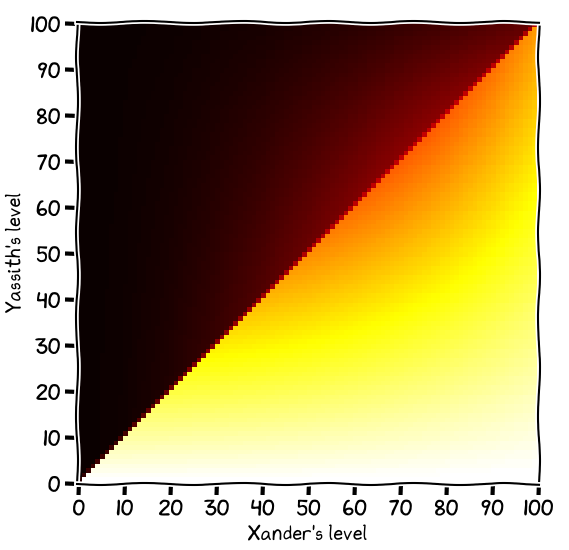

Here Xander’s skill level is along the X axis and Yassith’s skill level is along the Y axis. The colour shows Xander’s chance of winning the opposed roll; lighter is better.

There’s a very visible discontinuity along the line x = y. This is because a tie is only possible when both contenders have the same skill level.

Opposed rolls can have bonus or penalty dice. In fact, the rules say that bonus and penalty dice are primarily for use with opposed rolls, but I’m not sure I agree with that. I tend to think of the difficulty level of a skill roll as reflecting the inherent difficulty of the task (finding a book in a disorganised shop), regardless of conditions in which it is performed, and the bonus or penalty dice account for these extra environmental factors (needing to hide from a cultist).

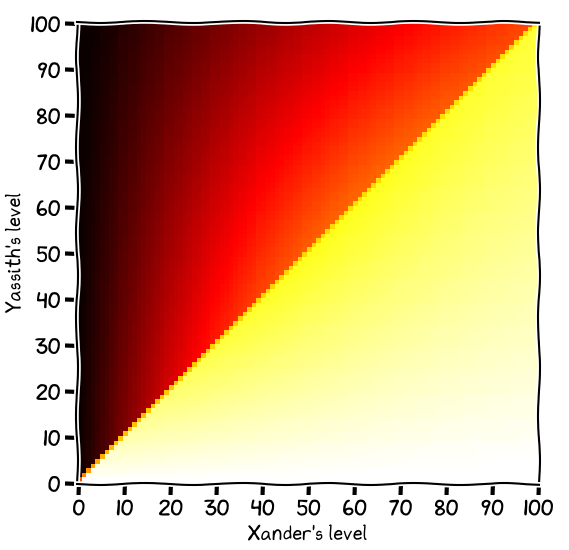

Xander might get a bonus die if he had a talisman which shielded him from the magic:

It looks pretty similar, but try comparing it side-by-side with the previous heatmap. It’s a bit brighter.

Alternatively, Xander might get a penalty die if he hadn’t slept well the night before, and was already not at his best:

Goodbye, Xander.

Four simple rules

This might all seem like a lot to keep in mind, but I try to remember these four rules:

-

Whether to call for a normal, hard, or extreme roll depends on the inherent difficulty of the task.

-

Bonus and penalty dice represent significant situational advantages or disadvantages.

-

Opposed rolls are for combat, magic, or if two PCs are directly competing. Use sparingly elsewhere.

-

Before rolling anything, ask if a roll is really needed here. If the task is difficult but the PC can spend as long on it as they want, shouldn’t they just automatically succeed?